|

To understand his professional demise, it is necessary to know

that Sandy Berman has always had a tendency to rant. Contributing to

the 1972 underground anthology Revolting Librarians, Berman

bemoaned at length the collections of most public libraries in the

U.S., which he characterized as stodgy preserves of the elite: "How

in hell can the pothead groove on Business Week and Norman

Vincent Peale? A feminist get excited over Cosmopolitan and

the Ladies Home Journal? Or an acid-rock fancier find any

goodies in the Reader's Digest? It ain't easy. Still,

longhaired freaks and madassed revolutionaries are as much members

of the community as Big Money Makers and hard-hat 'straights.'"

The

Chicago-born and Los Angeles-raised Berman was perhaps predisposed

to a touch of raucous crusading: "I would say that my folks were

good Roosevelt Democrats. It would be fair to characterize the

matrix that I grew up in as somewhat, okay, here's the key word

coming up, secular Jewish radicalism or liberalism." To

borrow a phrase from a speech he once heard I.F. Stone deliver,

Berman describes himself as "a pious Jewish atheist" who has long

been devoted to books, education, and the tip feather of left-wing

politics. The

Chicago-born and Los Angeles-raised Berman was perhaps predisposed

to a touch of raucous crusading: "I would say that my folks were

good Roosevelt Democrats. It would be fair to characterize the

matrix that I grew up in as somewhat, okay, here's the key word

coming up, secular Jewish radicalism or liberalism." To

borrow a phrase from a speech he once heard I.F. Stone deliver,

Berman describes himself as "a pious Jewish atheist" who has long

been devoted to books, education, and the tip feather of left-wing

politics.

After earning his master's degree in Washington, D.C., Berman

worked at libraries in that city and overseas, as a civilian for the

army in Germany during the Sixties. But what radicalized him, he

says, was his time in Zambia, where he lived with his two children

and his wife Lorraine Berman (she died five years ago, after

suffering a burst aneurysm in her brain). There he served as an

assistant librarian at the University of Zambia Library in Lusaka

for two years starting in November 1968. As in most libraries, the

collection there used Library of Congress subject headings, which

included the word kafirs to refer to black South Africans.

Several of his black colleagues told Berman that to be called

"kafir" was akin to being called "nigger" in America. An incensed

Berman investigated, and his research led him to question a host of

other labels used by libraries around the world--a line of inquiry

that pried the lid off a Pandora's box of controversial subject

headings and, eventually, established Berman's reputation as an

unyielding advocate for unbiased language.

The Washington, D.C.-based Library of Congress is the national

library of the U.S. Its classifications and cataloging of library

materials under various headings set the standard for how libraries

typically organize their stock and how users can find them through a

database. Berman launched his first full-scale assault on the

Library of Congress ("LC" in library parlance) in 1971, with the

publication of Prejudices and Antipathies: A Tract on the LC

Subject Heads Concerning People. Throughout the book, Berman

railed against what he took to be the Eurocentric,

Christian-oriented, male-dominated, establishment-pimping LC subject

headings. On the heading "Jewish Question," Berman wondered, "What

was (and in many places still is) the 'Jewish Question'? Who posed

the 'question'? And what kind of 'answer' did they furnish?" Berman

pressed on: "The phraseology is that of the oppressor, the ultimate

murderer, not the victim. Strong language? The stench of Auschwitz

was stronger." He concluded that the heading "richly merits

deletion" from the Library. The LC got around to doing just that,

some 12 years later, in 1983. Berman similarly suggested abolishing

the heading "Yellow Peril," which he placed "with gutter epithets

like 'slope,' 'gook,' and 'chink.'"

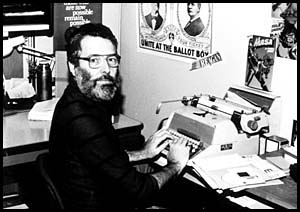

At work in

1973, Berman's first year as head cataloger for the Hennepin

County Library

Courtesy of Chris

Dodge | Agitating for such

deletions, and for positive additions, is a crusade Berman never

abandoned. In the decades after accepting the position of head

cataloger for Hennepin County in 1973, Berman frequently took to the

lecture circuit, offering his unconventional thoughts on library

issues at professional conferences and other venues. When delivering

speeches Berman would often rely on a light bulb as a prop, which he

would hold aloft and ask his audience to identify. Light bulb, you

say? Not to the Library of Congress, he'd explain, for whom the

correct answer is "electric lamp, incandescent." Such convoluted

labeling, Berman believed, did little to promote the nation's

16,000-plus public libraries as storehouses of knowledge designed

for citizens who know a light bulb when they see one.

Hennepin County first levied taxes for a library system in 1922;

today its 26 libraries have a combined annual budget of $29.2

million and about 700 employees. Serving more than 700,000 patrons

in the suburban metropolitan area, it is ranked as the 46th largest

system in the nation in terms of patronage. This year HCL was rated

as the fifth best large library in the U.S. by American

Libraries magazine. HCL acquires about 250,000 new items

annually, and its catalogers create some 30,000 new bibliographic

records every year. The 26 county libraries currently have at least

1.6 million materials on hand--books, CDs, videos, periodicals, all

detailed in a massive online catalog by author, editor, publisher,

publication date, page count, content description, and, of course,

subject headings--the most crucial means by which patrons are able

to find materials on the shelves.

It was at

his Hennepin County post that Berman opened another front in his

crusade by promoting the inclusion of hundreds of new subject

headings at the Library of Congress. In periodic memos to the LC

staff--memos that amounted over the years to a barrage--he proposed

innumerable headings as commonsense alternatives to the convoluted

language of the Library (for instance, "toilet" instead of "water

closet"). But what set Berman's course, and what set him apart as an

unorthodox cataloger, was the suggestion of entirely new categories

for the county's material--books and articles and new media Berman

and his Sandynistas identified as covering topics just coming into

existence in the world--computer-technology information, say. It was at

his Hennepin County post that Berman opened another front in his

crusade by promoting the inclusion of hundreds of new subject

headings at the Library of Congress. In periodic memos to the LC

staff--memos that amounted over the years to a barrage--he proposed

innumerable headings as commonsense alternatives to the convoluted

language of the Library (for instance, "toilet" instead of "water

closet"). But what set Berman's course, and what set him apart as an

unorthodox cataloger, was the suggestion of entirely new categories

for the county's material--books and articles and new media Berman

and his Sandynistas identified as covering topics just coming into

existence in the world--computer-technology information, say.

As head cataloger Berman would issue regular updates on new

subject headings created by his cataloging staff. The report for

April/June 1998 lists more than 200 terms, and it reads like a

veritable what's what of contemporary thought, a map by which to

explore the social frontier: Internet crime, anal fisting, bistro

cookbooks, country music festivals, dental dams, dog astronauts, gay

athletic coaches, Jewish-Canadian autobiographies, liquor industry

executives, narcoleptic women, new paradigm churches, Take Our

Daughters to Work Day, working class women's writings, xenophobia in

language, young Chinese-American women, suicide pacts.

Berman is quick to argue that he and his staff weren't in the

habit of creating subject headings just for the hell of it; rather,

it was work done in response to material that was already in the

database, but had been lumped in with stock where it didn't belong

or, more often, had been labeled in such a way as to make it nearly

impossible for patrons to find. "It doesn't mean that one approves

of anal fisting by virtue of having a book on it or creating a

subject heading for it," Berman reasons. "It just means that, look,

this is the theme, or the subject that's treated in this particular

material, and this is where it is." The objective, he stresses, was

simple: to fulfill the public library's mission--that of providing

patrons with information as readily as possible.

«PREVIOUS

PAGE || NEXT

PAGE»

|1

|2

|3

|4

|5

|6

|

|